AI guardrails and the sidewalks we forgot

By Angelica Ruzanova

In the 1953 piece “Golconda,” Rene Magritte depicts floating figures in a suburban environment - a somewhat staggering resemblance to the flowing impermanence, uniformity, and anonymity of digital platform inhabitants today. It is housed at the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas.

While walking past a poorly cemented pothole the other day, I thought of an interesting parallel between the traffic system and the regulatory space of artificial intelligence (AI). The metaphor passed through my mind like a thought in transit: if sidewalks indicate walkable cities and spaces that encourage community, exploration, and collective presence, why shouldn’t the legal infrastructure surrounding AI offer similar pathways?

It was a hopeful vision. Sidewalks, after all, have been around for thousands of years, whereas AI has only recently invaded highway billboards as we drive unimaginable speeds forward. Yet, sidewalks have also occupied a significant part of popular imagination; whether as crepidines separating Ancient Romans from chariots or the pedestrian paths of Mohenjo-daro, their modern emergence as a cornerstone of urban planning reflects the demands of rapid development. Not to mention, of course, their pristine emptiness amid the car-centric suburban ideal.

Philosophically speaking, sidewalks constitute the habitus of the flâneur - the urban pedestrian-observer, as coined by Walter Benjamin - whose experience of images and atmospheres depend on a walkable urban environment.

“In the person of the flaneur, the intelligentsia becomes acquainted with the marketplace. It surrenders itself to the market, thinking merely to look around; but in fact it is already seeking a buyer,” writes Benjamin in the “Passagen-Werk” (Arcades Project). This state of internalized preparedness to react to surroundings, to interact with passersby, and to experience a marketplace of ideas is but a hollow reminder while scrolling online.

What, then, could inspire an observer, a dweller of digital spaces today?

The abandoned sidewalks, alleys, and curbs of virtual systems take form more subtly than the pothole I stumbled upon this week. Modern technology embodies a more hidden form of discipline, as Michel Foucault describes, with which we lose the obvious manifestations of power. Moments of truth become abstracted, rendered scientific, and seemingly neutralized.

“He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself; he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection,” Foucault writes in “Discipline and Punish.” AI threatens to exacerbate these processes of self-surveillance.

Yet, my vision is not one of absolute repression and dystopia. I propose a new framework of user-friendly spaces online, as borrowed from healthy city planning principles of the World Health Organization, that foster physical, mental, and social well-being.

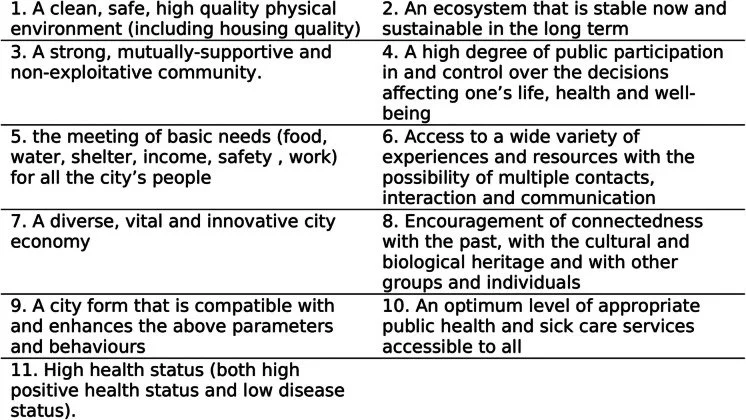

A set of 99 healthy city indicators for application in urban planning and design.

Walkability as Autonomy

The other day, I had the wonderful opportunity to sit down with Emily Liu, former Special Projects Director at Bluesky. Originally conceived as a decentralized protocol shared between platforms, Bluesky later evolved into a social media application following Twitter’s (now X) acquisition. With that history, it supports a decentralized network of hosted accounts, allowing users to retain agency and identity even as they voluntarily or involuntarily switch apps.

Could digital walkability be the ability to control one’s own data, algorithm, and shared third-party settings? Such mobility means reimagining the opaqueness that we see with social feeds today, and a radical clarification of how user-facing products are created and deployed.

Green Spaces as Balanced Use

One of the overlooked concerns in AI projects at this time is its strenuous energy demand, whether it be through data center grids or water cooling capacity. Studies have already shown that neighboring communities face challenges from ongoing constructions - a telling moment when digital storage begins to outpace physical resources – and more operations are in the works. These “beating hearts of the internet, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence” in cities like Phoenix, as the Stanford article suggests, is where employment tends to rise slower than the infrastructure to support them.

An approach worth exploring is the practice of permacomputing, a regenerative framework that encourages long-term sustainability of virtual work. A mutually-supportive, non-exploitative network that is compatible with all participating stakeholders, not merely the decision-makers behind-the-scenes.

Public Safety as Security

In a recent interview on the theme of trust, the Council on Tech and Social Cohesion emphasized upstream product design as an essential mechanism for fostering welfare in digital spaces. Just as pedestrian walkways, traffic signs, and speed limits shape physical safety in our cities, platforms implementing AI features must take a bottom-up approach in designing rules, processes, and pathways that will leave users with a sense of cyber-safety.

“Things like infinite scroll, autoplay, and engagement loops are finally being questioned,” said Jeff Allen, co-founder and chief research officer at the Integrity Institute.

A recent article by the New_ Public research and development lab echoes this concern, calling attention to the “unintentional business of fear” embedded in apps like Nextdoor, where crime-related content is consistently pushed above other kinds of community dialogue. This is where the knowledge gap between developers and regulators rings more apparent.

“There’s still a huge asymmetry,” said Allen. “Platforms understand how these systems work. Regulators and auditors are trying to catch up.”

To build ethical AI systems that reflect public interest, we must look beyond metrics of efficiency or scale. Safety, like sustainability, must be infrastructural. Not a retrofit, but a foundation.